Summary: Global food systems face rising pressures from climate change, conflict, inequality, and environmental degradation, worsening hunger and malnutrition. In India and beyond, sustainable solutions like agroecology, urban agriculture, innovation, and social safety nets can improve food security. Prioritizing inclusivity, resilience, and carbon-neutral practices is essential to feed a sustainable future.

We live in a complex world today – growing large-scale challenges like climate change, geo-political uncertainties, and income inequality, plague almost every part of the world. To navigate these challenges and ensure long-term sustainability and prosperity, systematic shifts are necessary. Even one of the most fundamental resources – food – is at the mercy of these global uncertainties. Within a span of three years, a global pandemic has exacerbated the hunger crisis, a war in Europe dramatically increased the food prices, and a series of extreme weather events has compromised our access to safe food!

Access to food has far-reaching implications for almost all aspects of global sustainability. The 2030 deadline to make our world free of hunger is fast approaching, and over the last three years, it looks like we are on an opposite track. Not just ‘Zero Hunger’, our food systems are a crucial component of our journey towards almost all of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The connection between food, social, and environmental systems is complex, yet it’s crucial that we understand this intricate relationship for a better tomorrow.

Growing global hunger

Our journey begins with a stark reminder of the global hunger crisis. Even before the pandemic, global efforts to fight hunger fell short of expectations, with over 61 crore people facing hunger. Then a series of disruptions like COVID-19, Russia-Ukrain war, and climate change-driven extreme weather events pushed an additional 12 crore people into a state of chronic hunger. By 2022, the number of people suffering from chronic hunger stood at a staggering 73.5 crore, as per the Global Sustainable Development Report 2023.

By 2030, nearly 60 crore people are projected to be chronically undernourished. In addition, an estimated 240 crore people are already facing moderate to severe food insecurity as of 2022, highlighting a lack of access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food. Regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and South Asia bear the brunt of this crisis.

With a ‘serious’ level of hunger as per the 2023 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 111th out of 125 countries. However, the Government of India has categorically rejected the methodology followed by Global Hunger Index, terming it as “a flawed measure of Hunger”! However, despite the lack of consensus on methodologies and indices, one cannot deny that the recent disruptions have had a significant impact on food security across the country. As per the UN data, the proportion of the Indian population suffering from hunger increased from 13.3% in 2018 to 16.3% in 2020, after decades of progress in reducing the hunger metric.

These statistics emphasize the urgency of addressing food system challenges worldwide. Despite a concentrated global push to end hunger and poverty, many countries, especially in Asia and Africa, continue to suffer. Now, the socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 and global geo-political conflicts have added a new layer of complexity to global food systems. India’s food sector stands at a crossroads — on the one hand, agriculture is one of the sectors worst affected by climate change, and on the other, unequal access, food wastage, fragmented landholdings, excessive use of chemicals, and loss of biodiversity continue to plague our food systems.

Climate change as a trigger

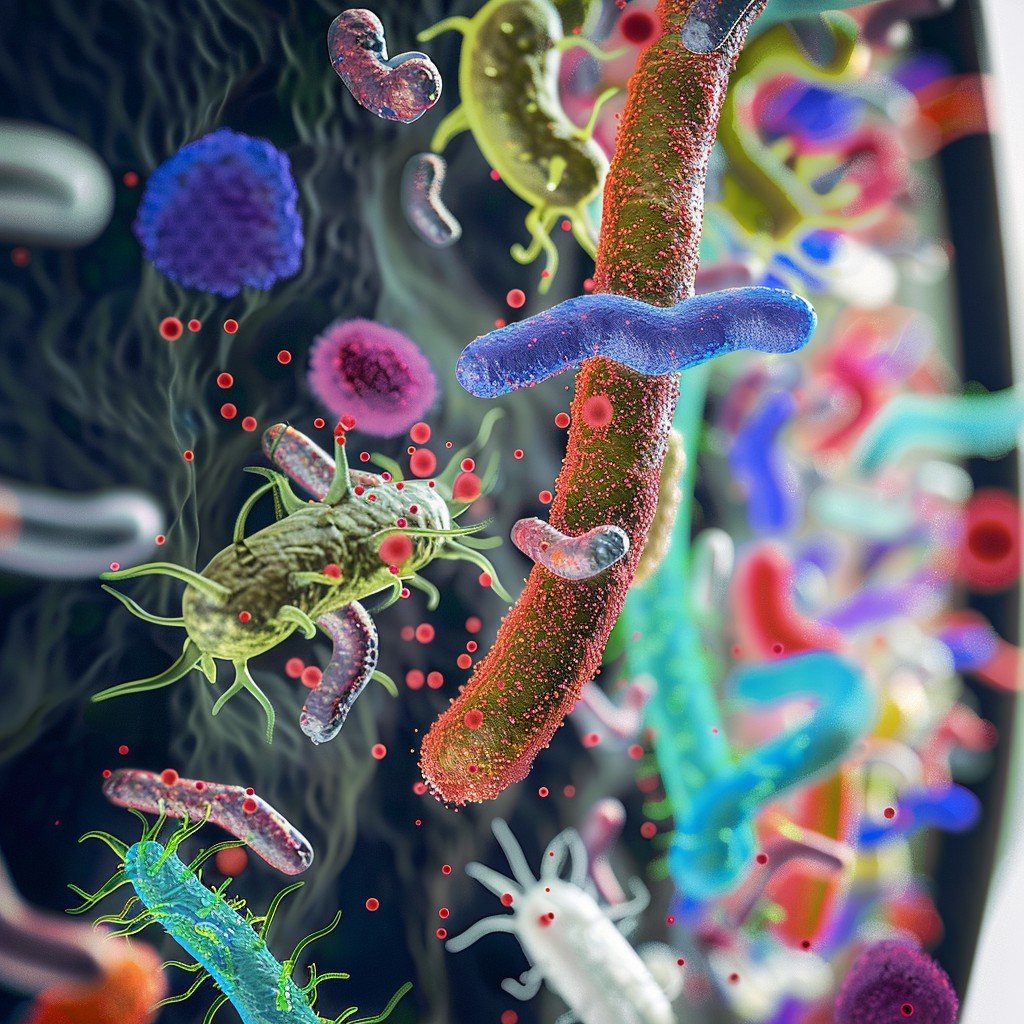

The link between food and socio-ecological systems is undeniable. Food systems are not isolated; they are intricately connected to the ecosystems on which they rely. Biodiversity loss, water scarcity, deforestation, land degradation, soil fertility loss, and pollution are becoming pervasive issues. The food sector is also a major contributor of global warming, and is estimated to account for 30% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Agriculture alone accounts for 18% of GHG emissions in India, while emissions from transportation, storage, wastage, and disposal of food need better tracking.

Climate change has been fuelling the global hunger crisis in recent decades, as it directly affects agricultural production. As the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events like droughts, floods, and cyclones increase, agricultural yields drop, food storage and distribution gets disrupted, and people lose access to safe food due to forced displacement. The degradation of land also threatens the resilience of the agricultural sector, ultimately impacting food security.

The increase in food prices raises a fundamental question: affordability versus nutrition. A growing body of evidence suggests that climate change is reducing the nutritional content of food crops. Also, as food prices rise due to climate change and geo-political stressors, people often resort to cheaper, less nutritious alternatives. This results in a growing incidence of malnutrition, which encompasses both obesity and micronutrient deficiencies. Such dietary changes can even contribute to an increase in non-communicable diseases like heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

Aggravating social injustice

An even more alarming trend is that climate change disproportionately affects women, children, and marginalized communities, in terms of access to safe food. Barriers are aplenty, limited landholding, lack of access to crucial agricultural inputs, technology, and information, unavailability of timely credit, and low negotiating power in economic and political relations, to name a few. Moreover, in patriarchal societies in particular, the majority of the dietary energy and protein is reserved for the male members of the family. So, in times of shortages, one can imagine the fate of nutritional security of women and girls.

As per the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, food insecurity disproportionately affects women and rural populations as rapid urbanization shapes agri-food systems and challenges the traditional rural-urban divide. In addition to worsening the hunger crisis, the pandemic widened the gender gap in food insecurity at the global level. Fortunately, now it has narrowed from 3.8 percentage points in 2021 to 2.4 percentage points in 2022. But given the ongoing geo-political tensions, growing number of extreme weather events, and their impact on global food security, such disproportionate impact on vulnerable populations is likely to exacerbate further.

Let’s talk remedies!

To tackle the multifaceted challenges of our global food systems, we need coherent, focused, widespread efforts from all stakeholders. Many entrepreneurs in urban areas are attempting to use innovations like hydroponics, aquaponics, vertical gardening, and synthetic foods to increase access to safe and nutritious food that has a lower environmental footprint. However, a pressing concern lingers: equitable access to these technologies. Without a balance between embracing innovation and ensuring inclusivity, sustainable food systems risk being elusive.

Strategies like system of rice intensification (SRI), laser land levelling, zero tillage, agroforestry, and organic farming are also being promoted, especially in rural areas, to increase the resource efficiency and crop yield. Many such methods, upon scientific implementation, are also proven to be effective in terms of reducing emissions and even sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. In India alone, as per recent estimates, the agriculture sector has the potential to reduce annual emissions by 85.5 megatonnes of carbon dioxide by 2030 using such farming practices.

Adaptation options in food systems can also prove to be practical tools to break the cycle of poverty and food insecurity and particularly benefit vulnerable groups. Social safety nets like subsidised food through Public Distribution Systems (PDS), or the Karnataka Government’s Gruha Lakshmi Scheme where women head of the family gets a monthly financial assistance of ₹ 2,000, can also build adaptive capacities of the poorest by addressing food insecurity and, consequently, rural poverty. Studies have shown that PDS can reduce the poverty intensity by 18-22% in India, while a well-functioning PDS could reduce it by up to 83% as shown in the case of Tamil Nadu.

The interconnected food systems challenges – climate change, hunger, biodiversity loss, unequal access to food, and land degradation – weave a complex web, necessitating holistic solutions. Addressing them may require a rural-urban continuum perspective, emphasizing connectivity across agri-food systems in urban, peri-urban, and rural areas. Crucially, public investment in research and development is vital to creating healthier food environments and increasing the availability and affordability of nutritious foods. Technology plays a pivotal role in boosting the capacity of urban and peri-urban agriculture in providing nutritious foods to urban areas.

Integrating urban agriculture into technical and scientific institutions like agricultural universities and skill-imparting institutions can help overcome the implementation challenges like lack of technical support, scale, and limited resources. Our research project “greening urban food systems”, supported by the Agence française de développement (AFD), examines how urban nature-based solutions (NbS) that provide ecosystem and societal benefits can help strengthen urban food systems. We experiment with co-production pathways across the science-policy-practice-citizen interface to scale up NbS around sustainable urban agricultural practices.

Even small-scale interventions like turning large campuses into food and biodiversity hubs or establishing food gardens in apartments, schools, or hospitals, can also go a long way in kick-starting our journey towards sustainable food systems. As local initiatives must take center stage, empowering marginalized communities plays a pivotal role, acknowledging that these approaches primarily benefit society’s most vulnerable. By creating inclusive spaces and providing equal opportunities, we can address disparities and foster resilience. Even the rapid urbanization in Asian and African countries, often seen as a challenge, offers income opportunities for women and youth while diversifying the availability of nutritious foods.

In conclusion, our global food systems are intricately connected with our social and environmental systems and face numerous challenges. Climate change, environmental degradation, and inequality are just a few demanding immediate attention. To build a sustainable and nourished future, we must prioritize carbon-neutral food systems, gender equality, inclusivity, and technical support. As we navigate the complex challenges of our current times, our choices today will shape the future of food security and nutrition for generations to come. By addressing these challenges head-on and implementing sustainable solutions, we can nourish the world and feed the future.